Why a physical board is better for Home Scrum

Why a physical board matters

I strongly recommend using a physical board for your Home Scrum system. There are dozens of digital Scrum board options (or column-based to-do lists)—the one most often used in the tech world is called Jira, and the most wide-spread free version is probably Trello. However, even when a team of developers uses a digital board, they will often maintain a duplicate copy of that board on a whiteboard or a wall near their desks. It’s almost ironic to see developers, whose entire job is to make virtual stuff, so dedicated to a physical object.

Why bother, though? Well. While digital options offer all sorts of fancy features and make things a lot ‘easier’ by being automatic and easy to rearrange, their big, big downside is that they’re not visible for most of the time. In fact, to make them visible you have to go through several steps—remembering it exists, deciding to refer to it, getting out your phone or going to your computer, tapping or clicking through several layers to go through the lock screen and app selection—and at every point, you add unnecessary potential for failure. These steps might seem so low-effort as to be laughable, but our brains are good at dismissing how significant a barrier a seemingly easy micro-action can be. Each one requires an active decision and a tiny bit of willpower to see through, while the status quo of your environment passively works against you—your device isn’t already in front of your eyes, and then your device offers a million other options for what to do instead.

Even when you’ve successfully opened your digital board and got it in front of you, your screen size might mean you can’t see it all at once, and navigating around it again takes some effort. Then changing things on it takes a few taps and some typing, which is never going to be quite as intuitive as grabbing a piece of paper and writing something down. I am actually a big fan of a lot of digital productivity aids (see this category of posts for a list of my favourites), but for the purpose of a Scrum board, they all fall short.

There might be a situation where a digital Scrum board is superior if you are doing Scrum with others who are not living with you. In that case, it is certainly easier to have a Scrum board you can screen share so that they can easily see what you’ve been doing. However, even then, I would probably prefer to make do with showing them your physical board via a camera.

There is a concept in modern, positive-reinforcement dog training around setting your dog up for success. You introduce a new skill to the dog in a quiet, distraction-free area, where the most interesting thing in their environment is you and your treats. You also break the skill down into smaller pieces. Essentially, you don’t expect the dog to manage too much at once. You do everything you can to avoid the dog failing (or doing an undesired behaviour) by setting up the environment in your favour.

Having a physical board sets you up to succeed with Scrum in a similar way. When you are in the same room with a constantly visible Scrum board, your environment is helping you. The only step involved in checking your board is to look around, or move over towards it. It immediately removes all of those extra steps that were acting as invisible barriers between you and an effective Scrum system.

Of course, the downside of a physical board is that you can’t take it with you when you’re out and about. How do you refer back to your tasks for the day while you’re out of the house, or in a different room? How do you capture tasks that you think of while you’re not near the board? I’ve addressed these problems in this post.

The environment’s influence on us: a rant

Having your Scrum board as a physical feature of your home is just one example of how the environment has a huge effect on how we behave, including whether we are able to function well and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Our society actually determines a lot about how disabling it is to have a physical or neurological difference.

‘The environment’ has come to mean ‘the planet’ or ‘nature.’ But I mean it here in the sense of ‘things around you.’ (‘Environ’ is from French and literally means ‘around’ or ‘thereabouts.’) So that includes your physical surroundings, like your own home, work-place, and town, but it also includes your cultural surroundings. Our mind is made up of connections which make meaning and stories out of our experiences and form our model of the world. So this, too, is a form of environment.

Ironically, it is from this cultural environment that those of us in the Western Hemisphere receive the story that we are all self-actualising individuals who make our own, independent choices about what to do with our lives. The extent to which the environment affects those choices is barely acknowledged. Even things which we genuinely like and want to do often come from deep cultural biases and expectations that have seeped into (and formed) our consciousness.

For instance, a lot of women enjoy the way their legs look and feel when they are completely smooth after being freshly shaved. However, most women have never actively tried the alternative of leaving their legs unshaved all the time, and if they do, they are swimming against the tide to learn to like the look and sensation of having hairy legs when society has such firm expectations that women ‘should’ have the opposite. (And, by the way, shaving takes about eight weeks and £6,500 over a woman’s lifetime—which is only one way in which women are expected to cultivate the way their bodies look.)

So, even our own desires, which feel so personal and spontaneous, cannot actually be trusted to come entirely from ‘us’. We can’t ever fully separate what makes up our opinions from the ideas we’ve grown up with, although it is rewarding work to try (and very necessary, in order to dismantle damaging concepts like racism and transphobia which have become embedded in our cultural infrastructure).

However, there is a positive flip-side to this, which is that by putting ourselves in a different environment we can influence how we act and think. This can be why travelling and living abroad can be so meaningful—we’re literally exposing ourselves to new sets of cultural meanings while simultaneously getting an external perspective on our own culture. It can help a lot with revealing where our blind spots and unexplored ideas are.

For example, while editing the posts for this blog, I took myself off to stay in a small student-style room in Manchester for a week, and spent each day travelling in to the centre to work on my laptop in a café. I am lucky enough to have a perfectly functional and pleasant study at home, which I worked hard to create and like very much, but I find it more difficult to work at home. Physically taking myself to somewhere else with the express purpose of focusing on the blog helped to shed all the other anxieties and obligations, which I would have found more difficult to separate myself from while at home.

For a more extreme example, consider how you would act if you were in a basic training camp for the army. You would wake up early every day, make your bed with military precision, polish your boots and iron your uniform, and keep yourself fit with lots of exercise. In short, you would seem extremely disciplined. However, practically all of this discipline is in direct response to the expectations placed on you from your environment, and the consequences you would face if you didn’t meet those expectations. The same person who thrives in this environment could have been (and could instantly revert to being) a total slob at home.

(On a related side-note, a lot of people with ADHD do well in the military. In fact, Francis originally tried to go into the army before trying to join the ambulance service. However, in recent years the UK military has decided that people with ADHD can only join if they are ‘free of symptoms and not requiring treatment for at least three years’, which is an absolute misunderstanding of how ADHD works—your brain will always be missing those neurotransmitters that the medication helps mitigate. This policy is a real shame, because a lot of people with ADHD would probably be fine without their medication while in the army, precisely because of how structured that environment is. I have even heard speculation from ADHD experts that people with ADHD have made excellent soldiers throughout history—they are more likely to take an impulsive risk, which leads to a higher likelihood of getting themselves killed, but also of battlefield heroics which might save your whole squadron.)

Our effect on the environment

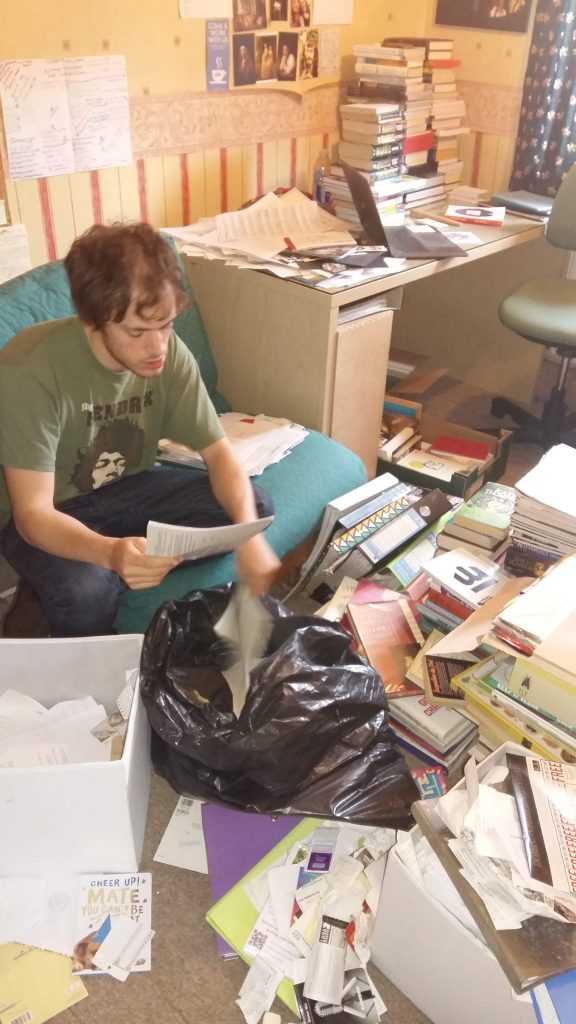

Just as the environment affects us, we affect our environment. In fact, we create it. We can see this most strongly in our living space: by and large, we’ve chosen where to live, and we’ve chosen the objects that live alongside us in our home. But then, why do so many people feel dissatisfied and sometimes outright overwhelmed by their own homes?

The problem is that we don’t get to start from a blank slate. I have often wished for external forces to swoop in and enact a complete reset of my environment (which is why I enjoy watching Queer Eye so much), because if I was already living in an ordered, minimalist, functional, elegantly-decorated house, I’m pretty confident I would have the skill and motivation to keep it that way. (It would also support other aspects of my lifestyle that I’d like to have, such as cooking more.) However, we’re all always starting from where we are, which in my case is: surrounded by a lifetime of clutter. And when there are hundreds of homeless objects around me, adding one more to the pile is the default action in that situation. Acting differently by trying to find a home for any one particular object often seems ludicrous in the face of the evidence of the rest of my environment.

Deliberately shaping our environment is much harder than we imagine it should be. In fact, it is another instance of the knowing-doing gap. We theoretically know how to change our homes and lifestyles to suit us, but most of us have fallen passively into habits which perpetuate the untidiness or disorder. Our status quo provides a heavy force of inertia that invisibly holds us back from the direction in which we would like to go. So while taking control of our own environment is a legitimate and effective path to change (and ideally would form an equal role in a treatment plan alongside medication to help people cope with ADHD and similar conditions), it is not going to happen without a systematic strategy, or without acknowledging how many barriers are built into your current environment which need to be tackled first.

Keep all this in mind as a reason to be kinder to yourself when you think that changing your situation shouldn’t be as difficult as it is. You can form an environment that will support you, but it will take work and a tactical dismantling of the things in your current environment that are holding you back. Without a strategic system like Scrum to help you stick to your chosen direction, you will probably get pulled back into your old ways of doing things. But we have found Home Scrum to be just the thing to break down the huge goal of changing our environment into manageable actions, and each step we take towards improving our home, career, or habits—our environment—makes our healthier lifestyle easier to sustain.