Feeling safe with others is a tricky business: power dynamics and drama triangles

When Google did some research on teams, the main, and really, only common factor among high-performing teams was a sense of ‘psychological safety.’ This meant that all team members felt able to be their true selves around each other, which allowed them to feel comfortable raising ideas and challenges. Considering what we saw about shame and disclosure, this makes total sense: only people who trust each other will let themselves be vulnerable enough to work through problems (especially personally meaningful problems) together.

But fostering this sense of safety in a group is a subtle and tricky business. Really, a huge swathe of psychology, psychotherapy, and sociology touches on the ways that human beings relate to each other, so we’re not going to go into all of it—but hopefully these thoughts below will give you a starting place for considering safety in your own Home Scrum team.

Boundaries

Having and communicating firm boundaries lie at the heart of all healthy relationships, but unfortunately this is rarely modelled well to us as children. I would recommend Anne Katherine’s books about boundaries as a starting point. I am still not great at asserting my own boundaries or even having a solid internal sense of where they are, but roughly speaking, it’s about knowing what you need to take personal responsibility for, and crucially, what you don’t. For instance, all sorts of manipulation and abuse come from confusing people’s sense of what is ‘their fault’: someone who claims “It’s your fault I’m angry!” is crossing a boundary, because other people’s emotions are not your responsibility to manage. However, as children, we may have resorted to attempting to manage other people’s emotions anyway, because that was our only way of staying relatively safe (e.g. by placating an angry parent with good behaviour). So trauma (another very important psychological concept that everyone would ideally be taught about) has a large effect on whether we know how to set healthy boundaries for ourselves.

The drama triangle

As a newbie to the idea of boundaries, this model is a very solid foundation to begin spotting places where people are crossing your boundaries or where you are not setting good ones for yourself.

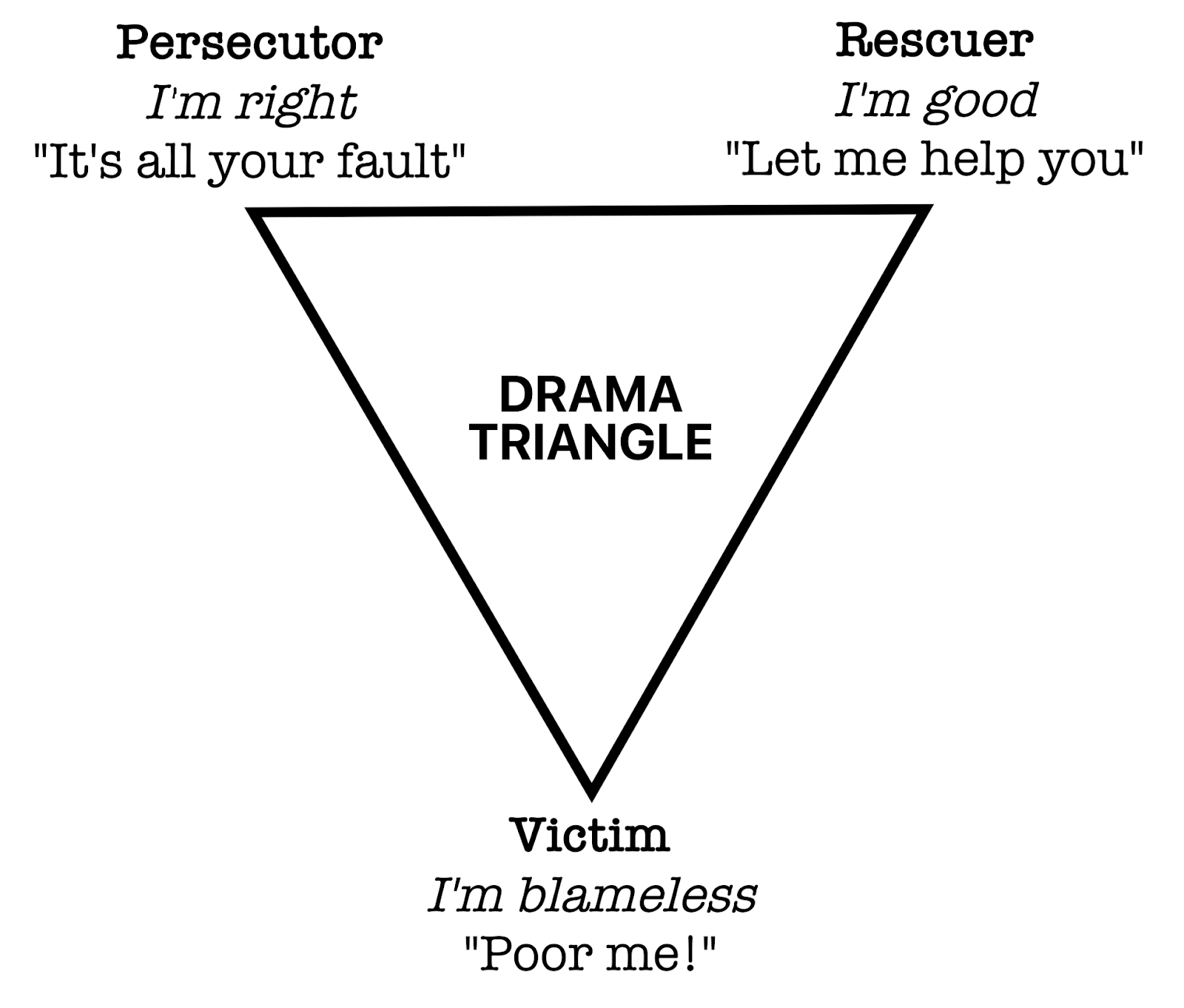

The ‘drama triangle’ is a highly useful mental model from psychotherapy. It was originally put forward in the late 1960s by Dr Stephen Karpman. It outlines an unhealthy pattern we can slip into when we relate to each other.

Say one person has a habit of acting victimised sometimes, when they feel overwhelmed; they believe they are helpless and incapable of meeting their responsibilities. You may often find that another person close to them then takes on the role of ‘rescuer,’ swooping in to try and fix all the victim’s problems. At first, this seems like a wholesome, positive interaction. But in reality, if we step back and take a wider view, we can see that the rescuer is encouraging the victim to stay in their helpless mentality by enabling them to avoid facing their problems. The rescuer will sooner or later start to resent the demands on their resources that they’ve allowed or imagined the victim to make. The victim comes to resent the rescuer coddling them and interfering with their autonomy. At this stage, either or both people can snap and switch into the ‘persecutor’ role, attacking the other. The other person may respond by fighting back in the persecutor role too, or slipping into the victim role, which then prompts the other to take on the rescuer. Either way, both people are still firmly on the drama triangle and caught up in a toxic cycle.

This scenario can play out between two or even three people, in ways ranging from subtle to all-out abusive. People might slip into it on a bad day, or remain cemented in it for their whole lives. It’s very human, but not inevitable; with self-awareness, counselling and practice, one can reach a new way of relating to others that is summed up in the opposite of the drama triangle: the ‘winners’ triangle’.

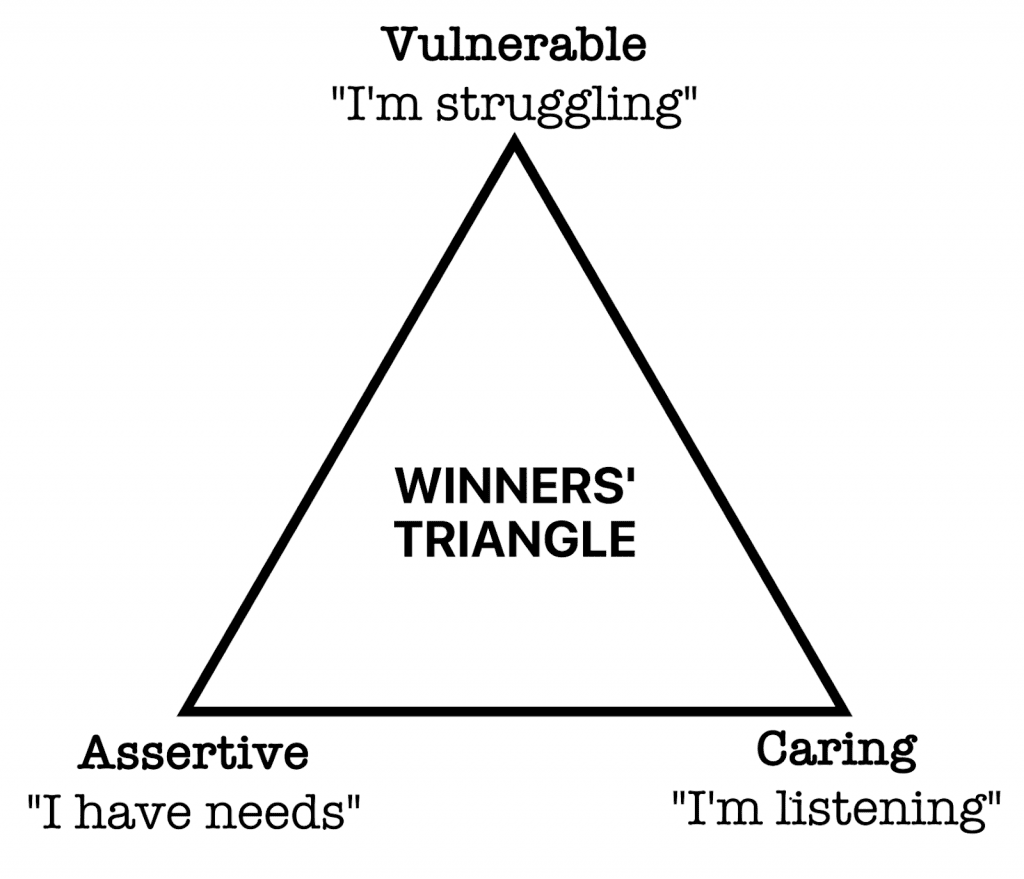

The winners’ triangle

The winners’ triangle (attributed to Acey Choy, who presented it in 1984) transforms each role into their healthier, underlying emotions. The victim becomes vulnerable; they are honest about feeling scared and uncertain while staying aware that they can still help themselves. The rescuer becomes caring; they offer support while not crossing boundaries. And the persecutor becomes assertive; they stand up for their own needs and boundaries without trampling over others’.

This is the balance we can aim for when we form our Home Scrum team. Asking for or offering help is not unhealthy, but we need to stay aware of whether the relationship is becoming martyr-like or leading to more dependence than interdependence.

Group dynamics and family roles

There is a woman called Thoraya Maronesy, whose channel I like to watch on YouTube. She asks strangers personal questions, like ‘What’s the most painful thing you’ve been told?’, and filming their responses. She also engineers conversations between complete strangers on the street. It is fascinating to watch people open up to each other in a way that they wouldn’t to anyone that knows them. It often feels easier to confide in a stranger than our own family. Friends might be a bit easier than family to talk to about our problems, again maybe for the same reason: they are slightly less close to us.

Why does this happen? Well, it could be partly down to what sociologists call group dynamics, which refers to how any group of people, whether a family or an organisation, will form its own internal system of relationships and roles within it, and that system become more fixed and settled over time. One way of describing this was put forward by Bruce Tuckman in 1965: that a group goes through stages of development—namely, ‘forming, storming, norming, performing’. During the ‘forming’ stage of a team, people will be getting to know each other and they might be remaining polite and slightly careful; ‘storming’ seems more chaotic because it’s when conflict arises among the team, but it actually shows that a bit more trust has been created and people are now comfortable enough to check and establish boundaries. ‘Norming’ is when things settle into predictable patterns, and at that point it’s possible for a team to start ‘performing’ to a high level.

If the composition of a group hasn’t changed in a long time, then people can have settled into very fixed roles. In a family, this is an all but inevitable, and not necessarily bad thing. But it can stifle change and innovation that is encouraged by the very nature of a Scrum system. Scrum can shake up and threaten the roles that each member of the team has adopted. Even unconsciously, we can find ourselves acting in ways that keep us held in those roles and sabotaging attempts by others in the group to leave their own. The complexity of all this is not helped by how our very sense of identity and self is deeply tied to how others (especially our family) perceive us.

One more fundamental element of any group dynamic is to consider the power imbalances between people—and there are pretty much always some. There is a power differential between adults and children, between counsellors and their clients, between bosses and employees, between those with more social standing and less (which covers a huge array of different social privileges, including race, gender, religion, and disability), between anyone who needs something from someone else. In a lot of cases, no-one is abusing that power, but it still affects the group dynamic and how safe each person feels suggesting a change to the status quo, even when no-one is conscious of there being a hierarchy present at all.

This is why I don’t want to assume that your closest family members will necessarily be best placed to be in your Home Scrum team. An important factor to consider is whether you feel truly safe enough with your family members to let them help plan your life. It is completely okay to ask people outside your household to be in your Home Scrum team instead, even (maybe especially) if someone in your family might take offence at not being asked to do it with you.

You don’t need to become an expert in psychology and sociology to successfully use Scrum with your own family. Pointing out a few of the many layers involved in relating well to other humans is not meant to alarm you or put you off. But it might be worth bearing all this complexity in mind, so that you can stay patient if you encounter resistance and push-back from yourself or others in your Scrum team to engaging with new ideas. Hopefully the space during Sprint Retrospectives is a good neutral ground for approaching these issues and their possible psychological root cause.

Especially for children and teenagers, allowing an evolution of roles within the family is a very healthy thing, and can really help with gradually allowing and encouraging more ownership and autonomy in their lives. Scrum, with its emphasis on constant iteration, is a great framework to use to make sure that the roles and relationships in your household are helping everyone to feel safe and not getting too static and stagnant.