How to plan (and how to make planning less overwhelming)

The purpose of planning

I used to think that the point of planning out my time was to fit more into my days. By cleverly combining certain errands into one trip, squeezing tasks in the spaces between fixed appointments, and deciding in advance which blocks of time would be used for what, I could increase my efficiency and therefore achieve, experience, and improve myself more. This approach is very tempting and addictive if you feel anxious, as it seems to promise a higher level of control and confidence than most people have over the way they spend their time. However, it can get overwhelming. From personal experience I can say this approach backfires in a massive way. It allows for escalating perfectionism, with all the pressure and burn-out that goes with it, and any brief feelings of control are illusory.

There is actually a diametrically opposed purpose for planning things: to figure out what things you don’t need to do. If you use your planning time to identify and eliminate unnecessary tasks, you cut out wasted effort before it happens, give yourself more space to do the things which are actually needed, put yourself under less pressure, and overall, simplify your life. So once again, we find ourselves with the theme of ‘letting go’ for this post.

The limits of planning

Although a fully written out schedule for your week can give the illusion of control over the future, it is important to acknowledge that fundamentally, trying to predict and shape how the future goes is, to a large extent, a futile exercise. Humans are bad at predictions. This goes for things like trying to guess what will be involved in completing a task and how long it will take, but it also goes for how you will feel at the time.

My counsellor gave me this analogy: say you are asked to choose from a menu in advance of a fancy dinner (perhaps at a wedding). When you make the choice a few weeks ahead, you might think you’ll definitely want the salad; but when it comes to the actual day, perhaps it’s miserable and cold and you got caught in the rain on the way there, and what you really want right now is the hearty casserole. There are just too many factors that go into shaping the current situation at any given moment, and even more factors involved in how you feel in response to that situation. You-in-the-present are always going to have more information than the naive you-in-the-past who made the plan.

Another analogy: when you’re planning, you’re like a general outlining a battle, but when you’re actually out there doing the tasks, you’re like a soldier on the ground. The soldier knows more about what’s really going on, and has to adapt the plan to the conditions found. Heaping more demands and expectations and rigid, pre-determined ‘solutions’ on the soldier does not help them in any way; in fact, it just increases the likelihood of overwhelm, panic and surrender. It is helpful to have a clear direction to aim for and an understanding of the purpose of that goal; then the soldier has all that they need to stay aligned with the desired outcome while changing their approach to suit the reality.

Given this, I try to allow for a lot more spontaneity and flexibility in my schedule than I ever did before. This does require leaving a lot of space for doing ‘nothing’ in the calendar, which grates against my deep-seated drive to increase efficiency. But given that nowadays I actually believe that doing less might be living more, I am more okay with this than I ever thought I could be.

With extra space built in, I have more room to respond to unforeseen factors that affect each day, such as how I’m feeling. I used to ruthlessly suppress my emotions as much as I could, so that they wouldn’t interfere with me getting on with my plan, but now, if I feel particularly overwhelmed or anxious one day (sometimes with no discernible cause), I am more often able to treat that as a valid reason for me to let go of my planned tasks for the day and leave them for a different time.

Of course, it does need to be said that there are times when it is healthy and necessary to coax ourselves into doing things which we don’t want to do, or feel scared of doing, because if we spend all our time avoiding tasks (procrastinating) then we are just engaging in another ineffective way to manage our emotions and to try and stay safely in our comfort zone, which will also lead to poor mental health. (For lots of little tricks and tools I use to help myself stay focused and get started on difficult tasks outside of just using Home Scrum, see the posts from this category.) Just remember that it is a balance, and there is no more virtue in forcing yourself to try and stick to a plan despite your emotions than there is in spending all your time in escapism mode in order to avoid your emotions. (If you do have a strong sense that being productive is somehow more morally virtuous than being idle, then you’re a victim of our post-Puritan, capitalist culture and need to look further into that belief.)

Why planning can feel overwhelming

To many people, it may seem like an obvious fact that planning feels overwhelming. But why? Well, as already explored above, a major reason could be perfectionism—that is, anxiety about whether you will be able to do enough, and do those things well enough, as well as the belief that something awful would happen (or it would mean something awful about you) if you let any of your commitments go. Trying to plan out my schedule often left me feeling more panicked than before, even though it also gave me a thin illusion of control and calm, because listing out every task I ‘had’ to do forced me to consider how it was basically impossible to manage them all, and increased the cognitive dissonance I felt as I tried to convince myself that there actually was enough space in my schedule to do them. (And even if, technically, there might have been enough minutes in the day for it all if I could turn myself into a machine, there was still the lurking knowledge that to do so would involve continuing to suppress all my fear, exhaustion, reluctance, anger, and needs for play, relaxation, socialising, and fun, not to mention exercise, sleep, and healthy meals, which amounted to a huge, unacknowledged cost that most of me didn’t want to pay.)

Another reason planning might feel overwhelming for you is if you have ADHD, or low levels of executive functioning for any other reason. If so, your ability to connect the tasks and plans you’re discussing to a desirable outcome in the distant future somewhere is dulled, and doesn’t feel emotionally meaningful. As such, the planning itself feels tedious beyond measure and also pointless, even if intellectually you understand what you could get from it.

Planning can also just be cognitively overwhelming, especially with weak executive functions. There are actually multiple steps involved in deciding which goal to go for, sketching out the path needed to reach that goal, imagining the sub-tasks for each of the steps in that path, and deciding which ones are necessary and which ones are nice-to-haves. And yet, most of the time we expect ourselves to hold all of this in mind at once while writing out a to-do list. This is why Home Scrum can be very helpful, in providing a physical way to represent each task and therefore making it easier to consider each task by itself. In general, this is an important principle to keep in mind to make planning less overwhelming: split each aspect of planning a task up so we can tackle things one at a time.

How Francis and I plan

First of all, we have recently decided on a time box (time limit) of one hour maximum for our Sprint Planning sessions. This makes it a much easier task for Francis (and me) to contemplate facing; even though the planning session feels dreadfully tedious to him, he can handle it if he knows it won’t be for an unknown or excessively drawn-out amount of time.

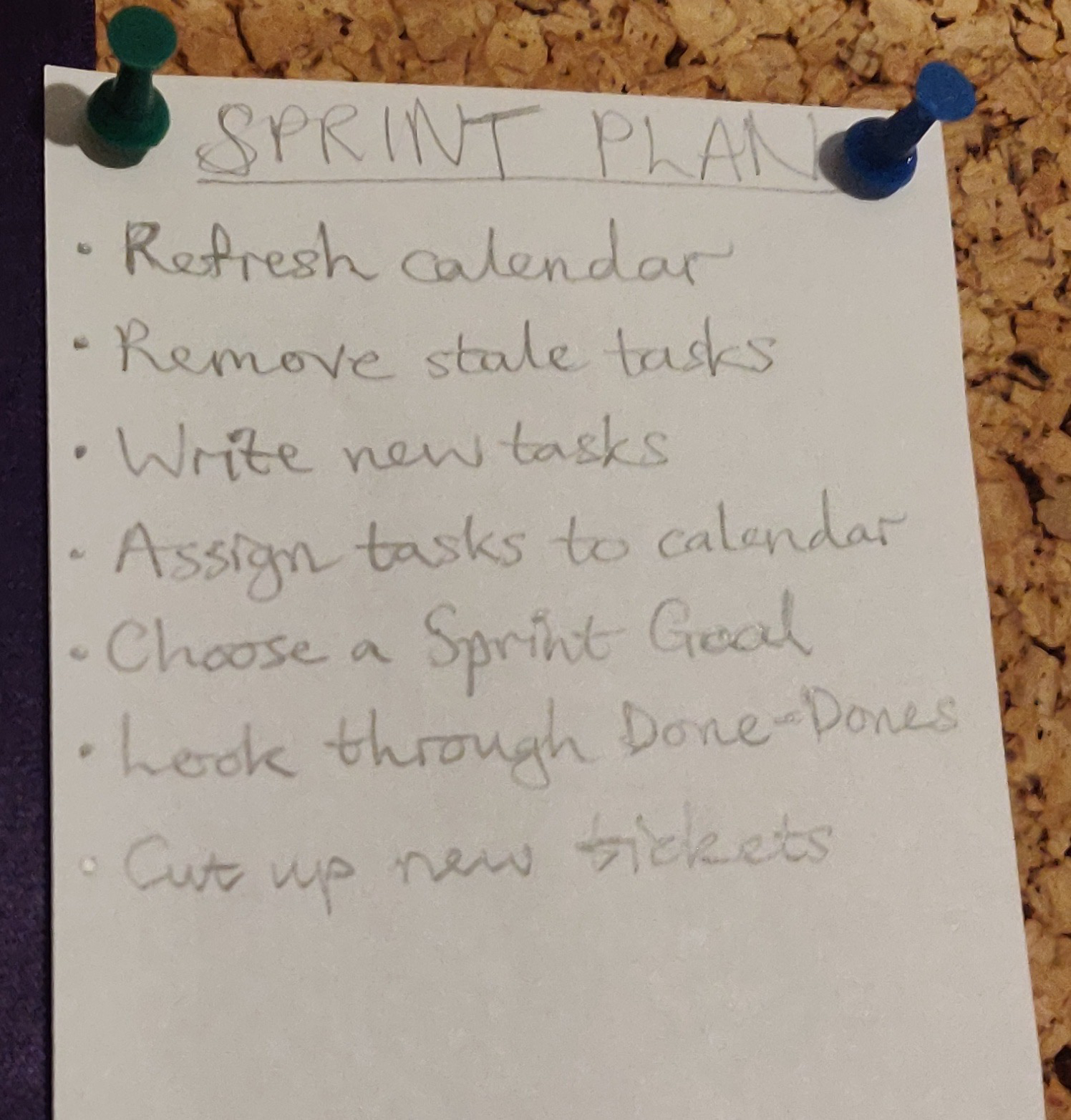

We also realised we were unclear on what exactly we’re supposed to get done in a Sprint Plan meeting, so we drew up this little template of an agenda, to remind us:

This is our current reference list up on our board for what to do during a Sprint Plan. Most of these seem self-explanatory, but here’s a quick overview:

- Refresh calendar: we write on the calendar with whiteboard markers, so we start planning by erasing all the previous days, and writing in new dates and any events we’ve missed from our online calendar.

- Remove stale tasks: see below.

- Write new tasks: if there’s any tasks related to events coming up, or just things we have been meaning to write down but haven’t, we quickly put them on the appropriate colour ticket and add a story-point number.

- Assign tasks to calendar: as in, take the tasks we’ve just written, or ones we’ve decided to do this sprint from our backlog, and move them onto the day on the calendar that we think we’ll have time to do them.

- Choose a Sprint Goal: see post.

- Look through Done-Dones: see post.

- Cut up new tickets: if our blank pieces of paper for new tickets are running low in any of the life categories, then this is a good opportunity to cut up more.

We’ve found that now the Sprint Plan is time-boxed, we have much less resistance to doing it once a week. And doing it weekly means there isn’t as much to get through, so going through the steps above only takes us about forty minutes rather than the full hour.

Letting go of ‘stale’ tasks

After using the board for a while, you may find that it fills up to the point where you just have too many tasks. At the start, Francis and I wrote down every project that we could think of to tackle in our lives, and we kept the long-term ones that we had no intention of doing any time soon in little piles in the backlog. We also wrote down every tiny task that we were doing, to get more story points (including things like ‘set an alarm for doing Daily Scrum tomorrow’ and ‘Count up story points in Daily Scrum’). That wasn’t a bad thing to do, but it’s something we don’t feel the need to do any more. The more tasks you have on the board, the more visual noise and clutter your brain has to parse, and that can quickly reduce how well you can get a picture of what you need to do from the board. Not to mention, it can feel overwhelming to see so many things you are supposed to do.

So I would recommend keeping it to things you are actively working on, and balancing keeping track of every little task against having space and clarity. One of the most important parts of keeping your backlog of tasks (and your whole board, actually) useful to you is being willing to let go of tasks easily. This again goes against those perfectionistic instincts which a) want to hoard all the shiny project ideas (what if this one is The One? The perfect project that will fix your anxiety and stress?), and b) hoard strong beliefs about grit and persistence and never giving up. But whatever productivity system you’re using, if you are not letting go of stale tasks, it will soon be swamped with tasks you don’t actually intend on doing which are just clogging up the system with guilt and noise.

We hadn’t used our Home Scrum system for a while, and the other day Francis and I approached our board, determined to rejuvenate it. We thought that would mean adjusting the column layout and finding some new and exciting board structure. What it actually turned out to mean was looking through every regular and non-regular task and evaluating if it was currently part of what we were actively doing or trying to do. Even without a clear view of our overarching goals at the moment, the results were stunning. The regulars especially went from crammed to beautifully stream-lined; there are only about twenty left. It has an amazing psychological effect to see the board so clean and empty—a bit like being ‘ahead’ on your goals, seeing that you don’t have that much to keep on top of makes things easier, and thus gives you more confidence. This is crucial and a wonderful effect of fighting to leave some space and breathing room in your task list.

So try to not worry too much about letting go of tasks; it can be hard, but is definitely worth it. You can always write out another task for it if you need to do it again. If a regular doesn’t actually happen that often, and doesn’t fit nicely into a slot on a calendar or something, then you can let it go and replace it when you next need to do that task. And if a one-off task has been hanging around in the backlog a long time, is it really something that you are aiming to do, or just an idea for a future project or goal? It’s okay to let go of those ideas too, sometimes, if you’re no longer interested in it; or if you are, then you could create an ‘Ideas’ section on your board and move the stale tasks there, so it’s clear that they are not ‘active’ at the moment. (You could even write them down in a notebook instead and reclaim the board space for current endeavours.)

With these tips and ideas, you already have plenty to go on in order to run your own Sprint Planning sessions. However, if you want more detail on how to break down and further refine tasks, then the rest of this blog post will be about that.

Before refining your tasks

Firstly, the prerequisites. Before we even get to the point where we have a task to break down into its component steps, ideally we will have addressed several things: what we even want from life, whether we’ve turned those desires into good goals, which goal we’re focusing on at the moment, and whether we’ve thought about the minimum viable version of our goal that we can iterate on. After all that, we will have a good idea of what outcome we’re hoping to achieve. Now we’re ready to look at the related tasks that we think will take us there, and check that they are broken down into small enough steps to make our path clear and less overwhelming.

That’s the ideal, but perhaps trying to think through so many steps of goal-refinement before we even get to task-refinement feels overwhelming in itself. If that’s the case, then heed the warning of your own emotions: trying to plan things ‘perfectly’ may be leading to more anxiety rather than less, so it is not worth it. You do not need to have a clear picture of where you’re heading in life in order to start getting some benefit from doing Home Scrum. You can start with the tasks which are right in front of you, stuff you’re doing already, and perhaps as each sprint goes by with a chance to reflect and experiment, you will begin to get a clearer picture of which parts of your life are going well, and which you want to examine more.

Sure, this ‘bottom-up’ approach might involve more time working on goals which ultimately turn out to be things you don’t want to do, and it will lack the efficiency of assessing and cutting out ‘dumb requirements’ at the outset. But it may be the only realistic way forward for you at the moment if contemplating your overall life direction feels like too much, and that’s okay.

How to break down a task into sub-tasks

Here’s a step-by-step guide of how to break down a task into do-able pieces. It’s actually a very subtle art, but one that self-help books often neglect to explain.

- Take the ticket down from the board. Say you have a task coming up on your calendar which is to go to your friend’s wedding. When you first knew about the wedding, you wrote it down on a ‘social’-coloured ticket, and put it onto the relevant day. But now it’s coming up in about three weeks and you’ve realised that ‘Go to so-and-so’s wedding’ is not actually a helpful breakdown of what you need to do to be prepared.

- Write down every relevant task you can think of onto separate tickets. Sit with the ‘Go to wedding’ task in front of you and brainstorm all the steps you might need to take to do it. Don’t worry about trying to judge how necessary each step might be at this stage—we are doing things one at a time. For going to a wedding, perhaps you would end up with a little heap of tickets in their appropriate category-colours saying things like, ‘Book a place to stay for the night,’ ‘Get the car fuelled up’, ‘Get the car tyres filled with air’, ‘Get the car serviced’, ‘Pack clothes and toiletries’, ‘Buy a new outfit’, ‘Get the suit dry-cleaned’, ‘Buy a wedding present’, ‘Wrap up wedding present’, ‘Buy a card’, ‘Write the card’, ‘Find a place for the dog to stay while we’re away’, and so on. The proliferation of tasks may feel overwhelming, and perhaps trying to visualise steps like this doesn’t come naturally to you, and you’re worried you’ve missed something. Well, these are good reasons to do this with someone else on your Home Scrum team, as they’ll help you think of things and help to prevent any worries from spiralling.

- Decide which tasks you don’t need to do. Take each ticket in turn and ask yourself, ‘Could I still go ahead and get the main task done if I didn’t do this task?’ So, could you still go to the wedding without doing the task? From the examples above, things like getting the car serviced and the car tyres refilled, and even things like getting a wedding present, card, and a new outfit or dry-cleaning the suit (if it’s not stained or smelly) would not prevent you from being there at the wedding if they didn’t get done. You can always keep these in a little pile to come back to later if you still have time after doing the essential things. Hopefully, after this step, you feel a bit calmer. For more on this step and how to prioritise a list of tasks, see the next section below.

- Add story points to each remaining task (optional). Run through the important/necessary tasks and add a number in a circle in the corner of each ticket to represent how much effort you expect it to take.

- Decide on which order to do the tasks in. Some tasks will make logical sense as a step that can only be done after a different step. Some tasks will work well or only be possible on a certain day when you have the time, for instance using a weekend to go shopping for a present or outfit (if you still want to do this). Some tasks are more urgent and need to be done sooner (asking someone to look after the dog, finding somewhere to stay), and some could be done in the days before or even on the day (packing, fuelling the car). These tasks can go onto the calendar for when you think you’ll do them.

And that’s it—now you have a solid plan, with assurance that the essentials will be covered, and any extra tasks defined but not overwhelming you. That’s how to break down a task in a helpful, brain-friendly way.

How to prioritise tasks

There is a lot that could be said about prioritising. Answering the question of what you’ll give the most importance is actually at the heart of managing time and life and living well. So, correspondingly, it’s also the hardest and most nebulous part of the whole process.

At least at the individual task level, there is a very handy acronym that can help called ‘MoSCoW’. This stands for Must, Should, Could, Won’t. So how it works is that you ask yourself in relation to your goal: would I still be able to reach the Minimum Viable Product without this? If the answer is ‘absolutely not’ then that task is a true ‘Must’. If you could manage without it, but to do so would mean dealing with some amount of ongoing difficulty and nasty work-arounds, then it’s a ‘Should’. If the goal would work just fine without this task, but that task would still be a nice-to-have, then it’s a ‘Could’. And if you realise that a task is actually just adding a distraction that you don’t need when going for your goal then it’s a ‘Won’t’. You can add an ‘M’, ’S’, ‘C’ or ‘W’ in the corner of each task and sort them into piles or columns respectively, and you will almost always find that there aren’t actually as many Musts as you thought.

You would think (or at least I did) that you would already know which tasks are important and which aren’t at the stage where you’re creating the tasks and breaking down your larger goal. But this comes back to the principle of doing one thing at a time; coming up with the tasks and then actually thinking about the relative priorities of those tasks are different mental processes, and you’re unlikely to be able to do them simultaneously or to hold all the results in your head. By putting it all out onto the paper tickets, you can get so much further, as each separate mental process can be done as its own, manageable step, and the results of each mental process are captured externally for further review.

Of course, prioritising every task like this adds another chunk of effort into your sprint plan meeting, and Francis and I rarely remember (or can be bothered) to apply this method to our tasks. I think it works best when you have a bunch of tasks all related to a particular goal, so you don’t necessarily have to use it all the time. But when I have been stressed in the past about a goal, and my perfectionism has been hard at work generating lots and lots of extra tasks I could do to make the goal better, breaking it all down and then looking at each piece separately with the question, ‘Could I go ahead without this done?’ is an incredibly calming and grounding exercise.

Make sure you break down any tasks which feel intimidating

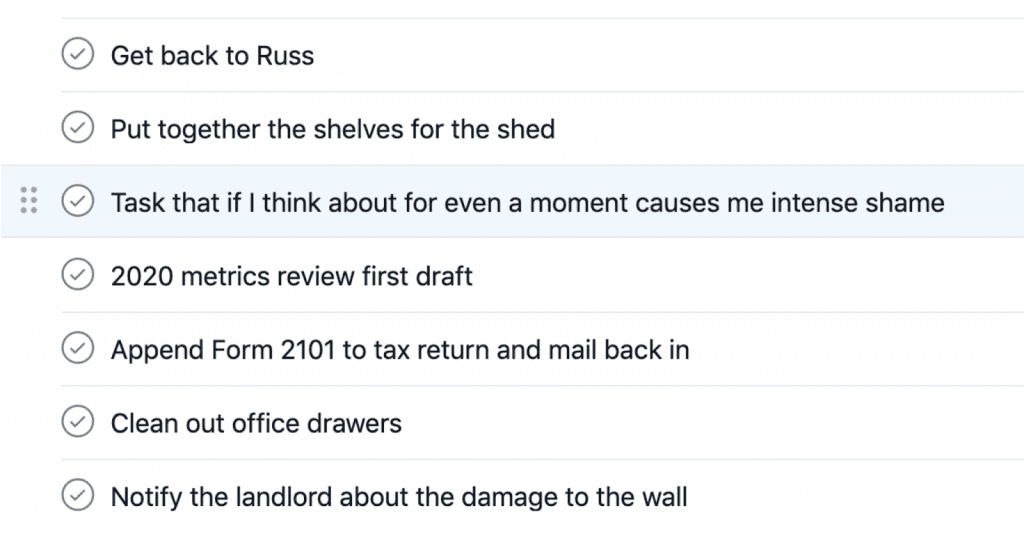

Sometimes there are tasks which, for no particular reason, feel very scary to think about doing.

As the picture above says, it all comes down to shame. Sometimes some things link in our head with significant meanings about doing it or not doing it. If we do it, and succeed, we’ll be good enough; if we fail, we won’t be good enough, and might provoke others’ disappointment or anger. Not doing it might also do that, but less immediately, or at least we can avoid thinking about it, which we can’t if we’re actually doing the task, and facing that possibility is really scary.

Robert Wiblin, the Director of Research at 80,000 Hours (which gives advice for how to do the most good with your career) calls these tasks ‘Ugh Fields.’ It could be any task that starts off unpleasant or difficult to face, and only gets more so over time, and as it goes along it gets painful to even think about, so in the end you’re not even thinking about the task itself, but rather about how painful it is, which completely blocks up your thought patterns around alternatives or workarounds which would get the situation unstuck and resolved.

You may be able to physically notice these emotions just by seeing which tasks on your board you struggle to look at or contemplate. If so, be very gentle and compassionate with yourself; congratulate yourself for even noticing which tasks are causing you this issue. Then, with the other member(s) of your Home Scrum team, have them help you think or talk through whether there is a way to completely drop that task, or do some lesser version of it, so that you no longer have to be living in pain or fear of it. There might even be an opportunity to ‘swap’ Ugh Field tasks between you and another member of your team, as long as you both feel happy about tackling the other one instead. It’ll often be easier to do someone else’s Ugh Field task for them, because you don’t have the toxic emotional attachment to it where you’ve been avoiding thinking about it for ages.

In general, for any task where you have a strong reaction or feel the pull of wanting to evade doing it, see if, first of all, you can’t sometimes give yourself a break by accommodating that impulse and getting rid of the task somehow. It’s unlikely that any single task is worth more than your mental health. If it does have to get done, then a simple way to get things moving is to break it down into its sub-tasks and add those to the board instead. First of all, the sub-tasks will be a bit less scary because they’re smaller, but also because they’re concrete. If you’ve defined the next specific action to take, then you can probably actually picture yourself doing that, and it might feel less impossible to achieve. This is the healthy side of planning: if used wisely, planning can help life feel less overwhelming.