Sprints and Sprint Goals

What is a sprint?

As stated in the introductory post, a sprint refers to the time-cycle in Scrum at the end of which you have your Sprint Review, Sprint Retrospective and Sprint Planning for the next one. They are meant to shorten how long it takes for work to be shown to the stakeholders—if stakeholders get to see how the work is going regularly then they also get to give feedback regularly, and this means that goals can be adjusted to suit reality as the team goes along.

How long is a sprint?

The official Scrum guide states that a sprint can be “one month or less.” The shorter the cycle of sprints is, the more often you get the opportunity to inspect and adapt how things are going. At work, nearly everyone uses two-week sprints. We did at home for a while too, but then switched to weekly, since life is pretty much set up into weekly sprints anyway.

However, we’ve had difficulty actually running a retro, sprint planning and review meeting every weekend, or even every month. If you think you might too, then it might be worth making your sprints longer, with the caveat that the retro, sprint plan and review are taken seriously and fully committed to when they come along.

Sprint goals

I’ve talked about different types of goal, and what makes a good one, but I didn’t explicitly mention where goals fit into Scrum. The answer is: by setting sprint goals.

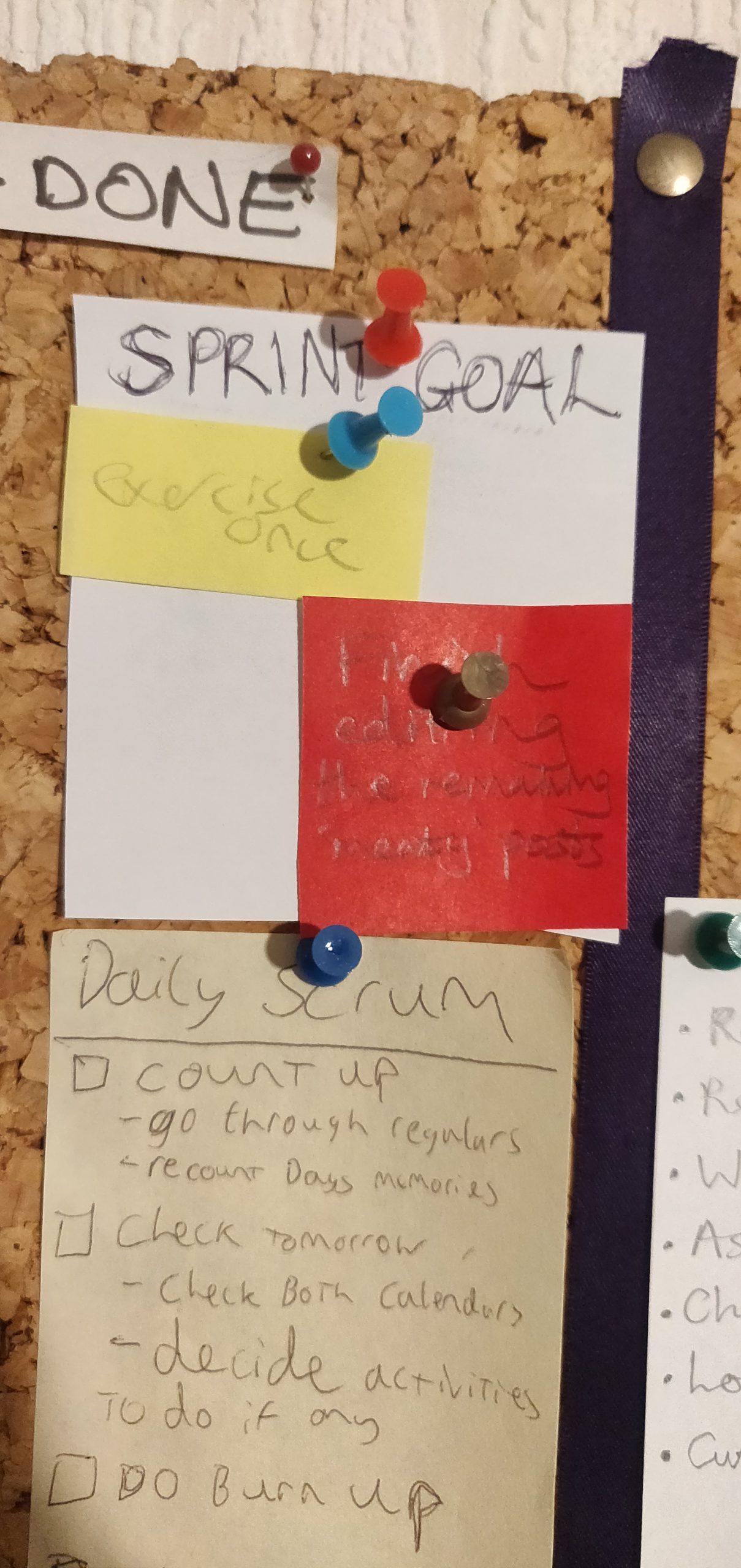

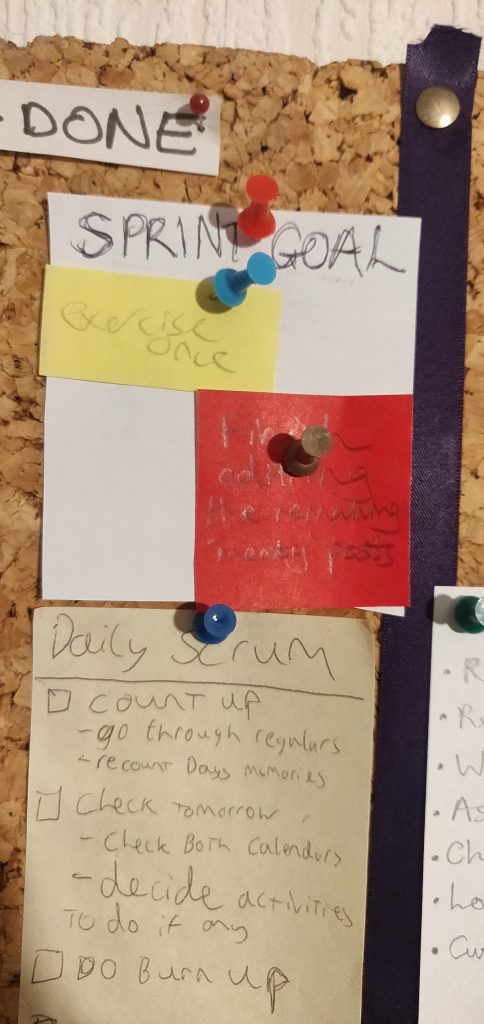

Having a goal for your sprint gives the team a sense of purpose and focus that isn’t really possible when just trying to get through a bunch of unrelated (and unrelenting) tasks. Writing that goal down and displaying it somewhere prominent on your board will help you to check in throughout the sprint and see how you’re doing regarding getting it done. Likely you will also have other tasks that you have to do too, but your sprint goal should be your top priority.

We haven’t actually tried using sprint goals in this way ourselves yet, but recently we’ve decided to try giving each week a ‘theme’ from a life category. In particular, we think we will rotate around weeks themed on doing a House goal, a Health goal, and a Hobbies goal, with the other categories getting an occasional week every so often. This will help us have a framework for deciding what to focus on, as figuring out a top priority to focus on is often not that clear at work, let alone in life.

Sprints are supposed to be closed units

So, let’s talk about time boxing. When you do your Daily Scrum, you have a time box of fifteen minutes: a maximum length of time to spend on doing it. That’s all a time box really is, but they can be very effective at every scale. At the level of fifteen minutes, it keeps everyone focused enough to omit extraneous detail and stick to the main job at hand. This is also how it’s supposed to work at the level of a sprint.

A sprint is more than just the length of time you do Scrum for before you have your next retro, planning session and review. It is also a time box: you are supposed to decide at the start of the sprint what goal to focus on during this time, and therefore what tasks you need to bring in, and then not let any new tasks into your sprint. It’s a closed unit, which means that the team can buckle down and give their entire attention to doing what you all said you’d do, and not get distracted by anything else.

It’s a great idea in principle, but I admit that Francis and I have never been able to stick to it in practice. In fact, this is the part of the Scrum system that also gets broken the most at work. There’s just always something that comes up to do, and often it needs to be done before the end of the current sprint.

To mitigate this, I’ve been advised that there are two possibilities: either you can stand firm against the surprise task and say ‘no’ to bringing it in to your current sprint’s to-do column because it isn’t related to your sprint goal (another good reason to have a sprint goal, so you can measure new demands against a clear priority), or you can deliberately not take so many tasks into your sprint, so you have room for contingencies. This last is probably a good idea in any case, because humans often overestimate how many tasks they can get done, and it’s good to try and limit yourself to what is realistic. A final option is to deliberately adopt elements of a similar system called Kanban, which allows for a constant flow of tasks, although that also requires a constant process of reprioritisation.

I think it is worth doing your best to stick to a pre-decided Sprint Goal and set of tasks for your sprint, because I think Francis and I do lose out on a powerful part of the Scrum framework by not attempting to keep each sprint as a closed unit. It means you get a proper chance during each planning session to readjust your direction (inspect and adapt what you’re aiming for), as well as to properly assess what size goal and how much work is reasonable to attempt over the next sprint. There is something very comforting about having a defined subset of tasks that you need to do (and know you can do), rather than constantly having the whole lot drifting in and out of your to-do column.