The iterative method of practising

How to practise a physical skill

As a child, teenager and young adult, I spent a lot of time practising violin and piano. As I have discussed elsewhere, I think the approach I took was far too rigid and results-focused, and learning through play and improvisation should nearly always be the preferred method for picking up a new skill. However, I did learn a lot about how to efficiently and effectively practise a physical skill to a high level of precision, and if you are trying to do that too, then here are the conclusions from my own experience.

Essentially, good practice is a blend of mindfulness and experimentation. It takes a lot of mental discipline to maintain this curious, focused frame of mind, but if you can (and you don’t have all the mental hang-ups that I did around feeling anxious about it all), it can be an extremely meditative and satisfying process.

What I mean by experimentation is to apply the scientific method to what you are trying to do. First, isolate a fragment of what you are trying to learn (just one movement of your hand between positions on the piano keys, for instance), then try to do it, and see what your result is. If that result is not what you were hoping for, then analyse what about it was and wasn’t correct, form a hypothesis about what you need to change, and then try again.

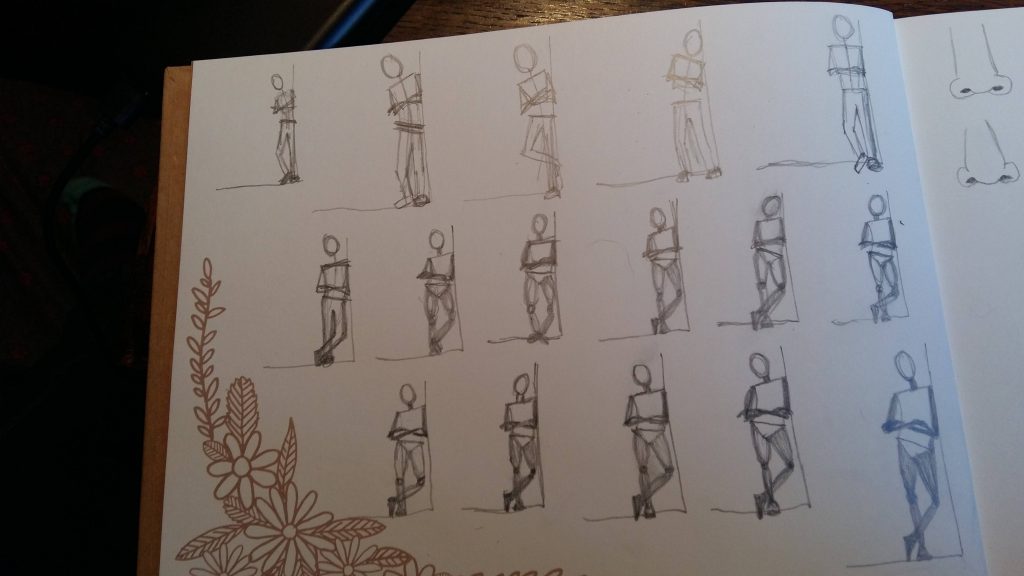

I found a good example of this for learning how to draw. This video describes an approach called ‘iterative drawing’, where you repeatedly try to draw just one small thing, and keep checking back in with yourself about whether it looks right or not. You can then draw it again, consciously trying something slightly different (like ‘maybe I need the front leg to be further forward…’) and see how that works. Your brain gives you instant feedback on what works and what doesn’t, and eventually, you figure out an approach that works for you. This is a far, far more solid way to learn than following someone else’s instructions on how to draw something, or even copying a reference image again and again.

The way I (eventually) practised piano was similarly experimental. (I learned this method from the same piano teacher who eventually persuaded me to take a ‘sabbatical’ from piano and violin, as he could see what a toll it was taking on me.) The key point to get the most out of practising this way is to play the piece exactly how you want it to sound in your final performance; at full speed, with both hands, and with the highest degree of accuracy. (The way I had always been taught to practise previously was to learn one hand at a time, then slowly put them together, and then gradually bring the piece up to speed.) How can you possibly play up to a performance standard when you’re just learning the piece, though? By adjusting the variable of how much of the piece you are trying to play. You take the literal tiniest slice of the music you possibly can—usually only two notes, or chords—and zero in on that one single movement of your hands until you can do it flawlessly. Then, slowly, these micro-slices of the piece are stitched together with the surrounding slices, until you can play straight through with perfect accuracy.

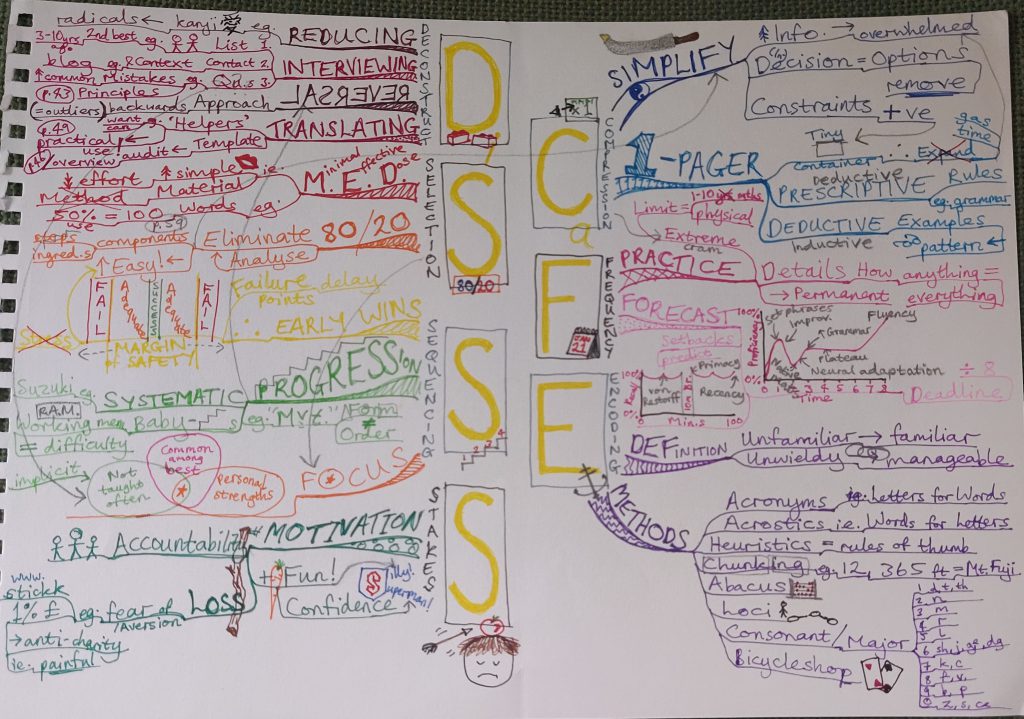

If you find learning how to learn interesting, I would recommend reading the analysis of the steps involved that Tim Ferriss wrote in his book The Four Hour Chef. I made a mind-map of his main points here: