Perfectionism: the destroyer of worlds

Do you plan too much? Are you always trying to optimise every part of your life but struggling to get any of it done? There is an old Italian proverb: “Le meglio è l’inimico del bene”—“the best is the enemy of the good.” I would go further. I would say that perfectionism is the destroyer of worlds: of happiness, self-esteem, contentment. It is the enemy of peace, joy and goodness in life. Let us stand up to this scourge and fight back!

My experience with perfectionism

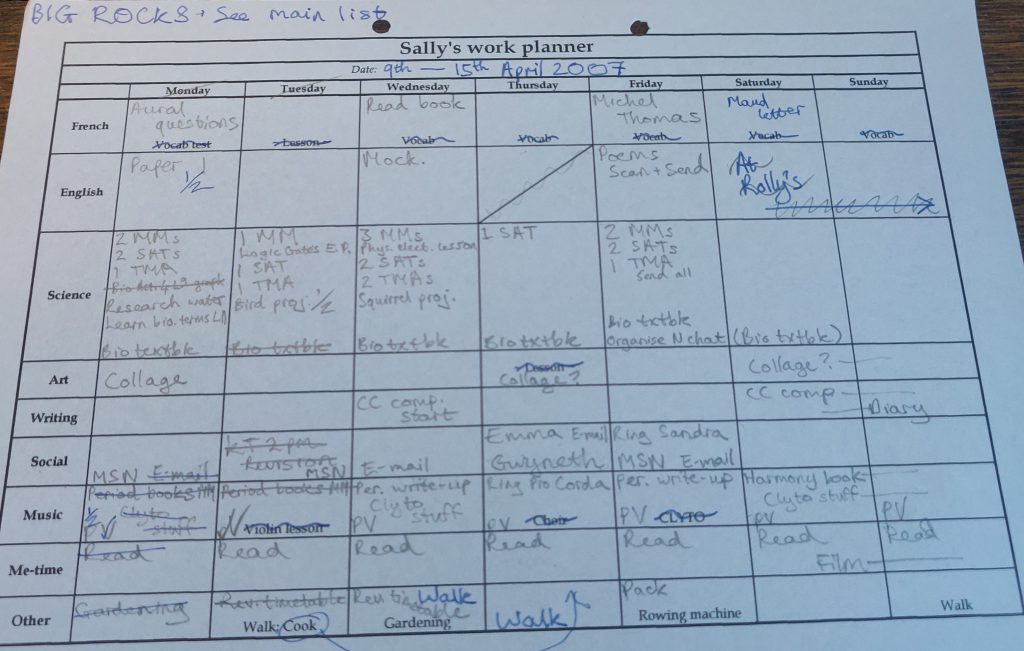

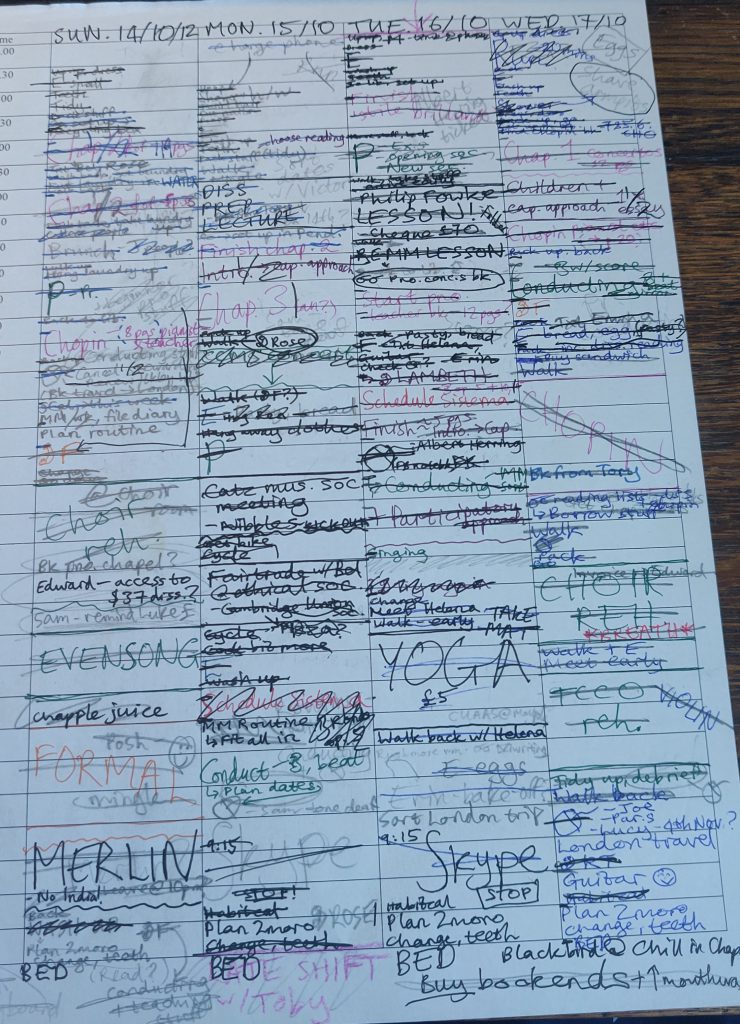

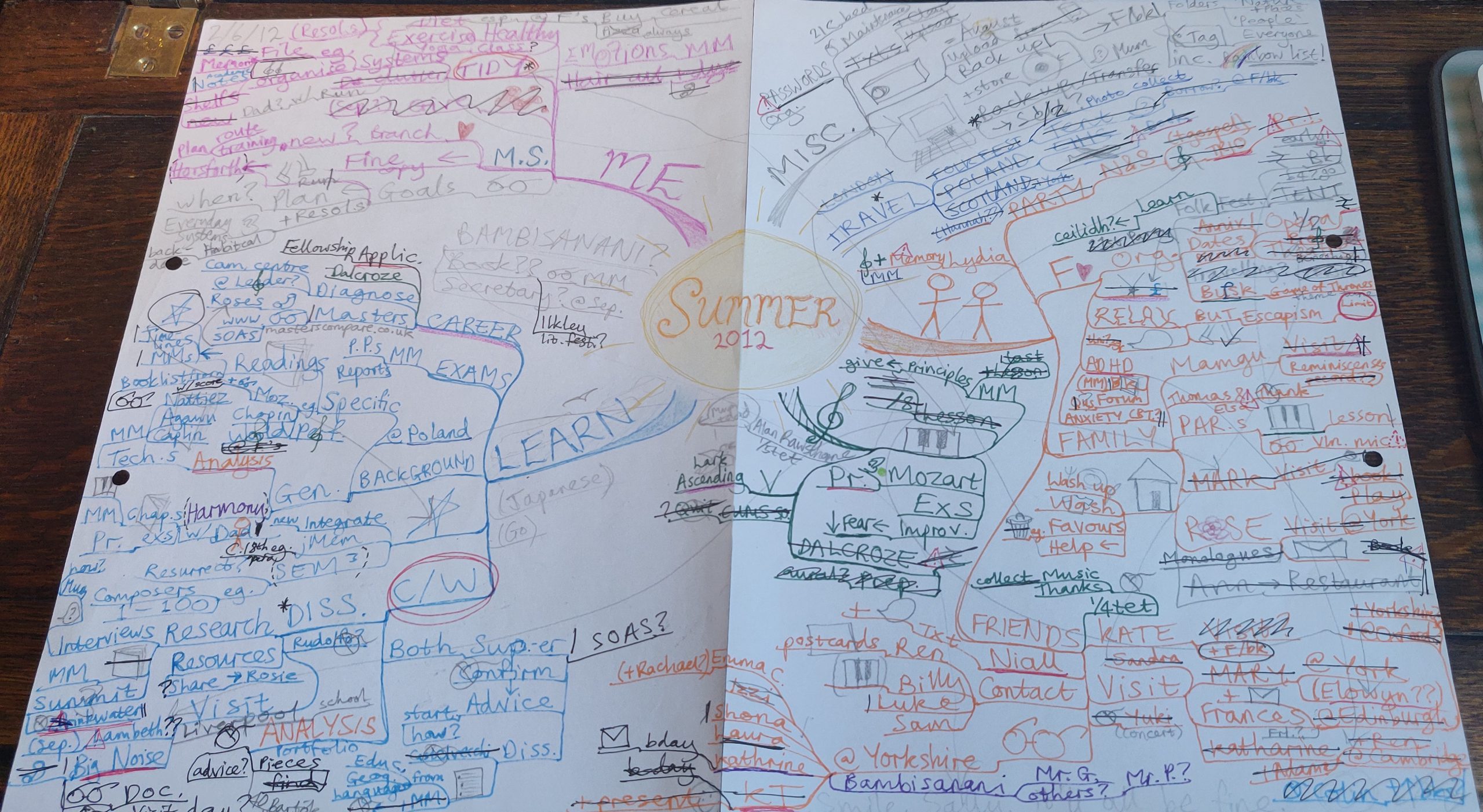

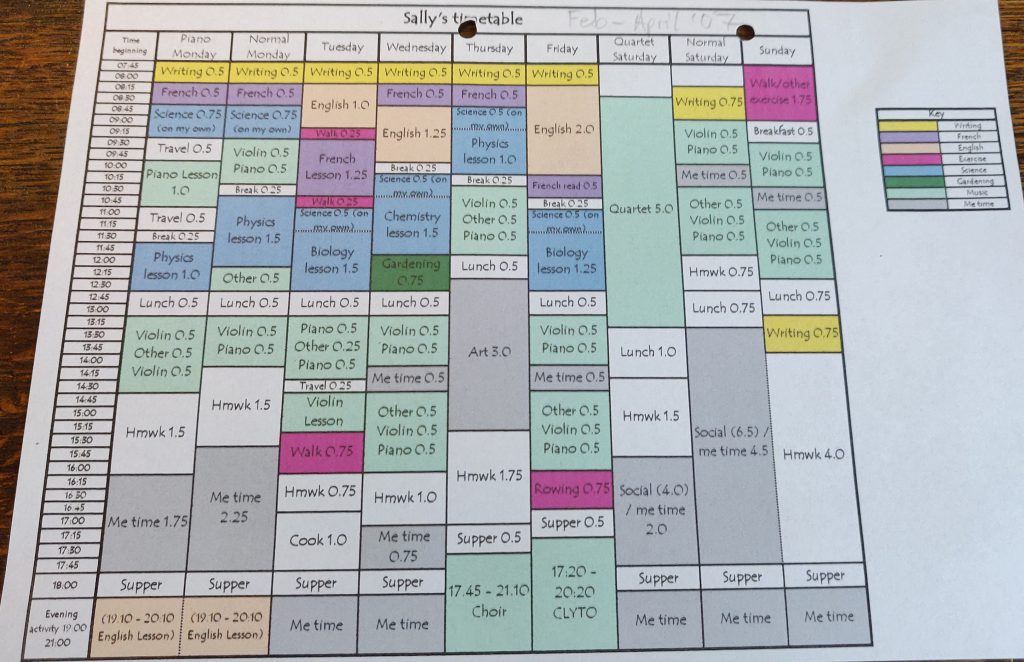

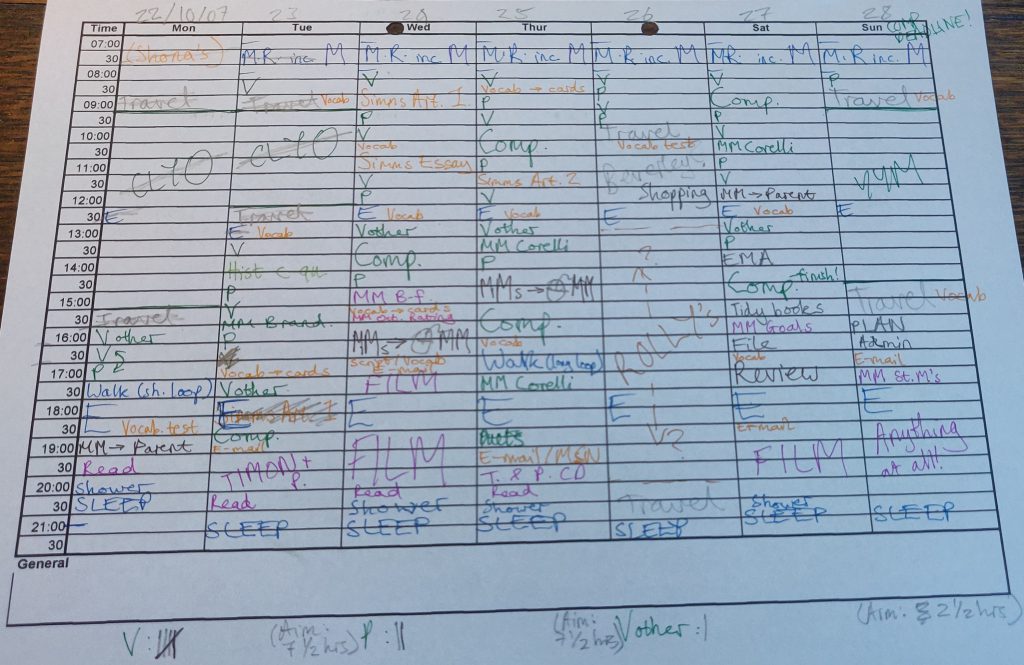

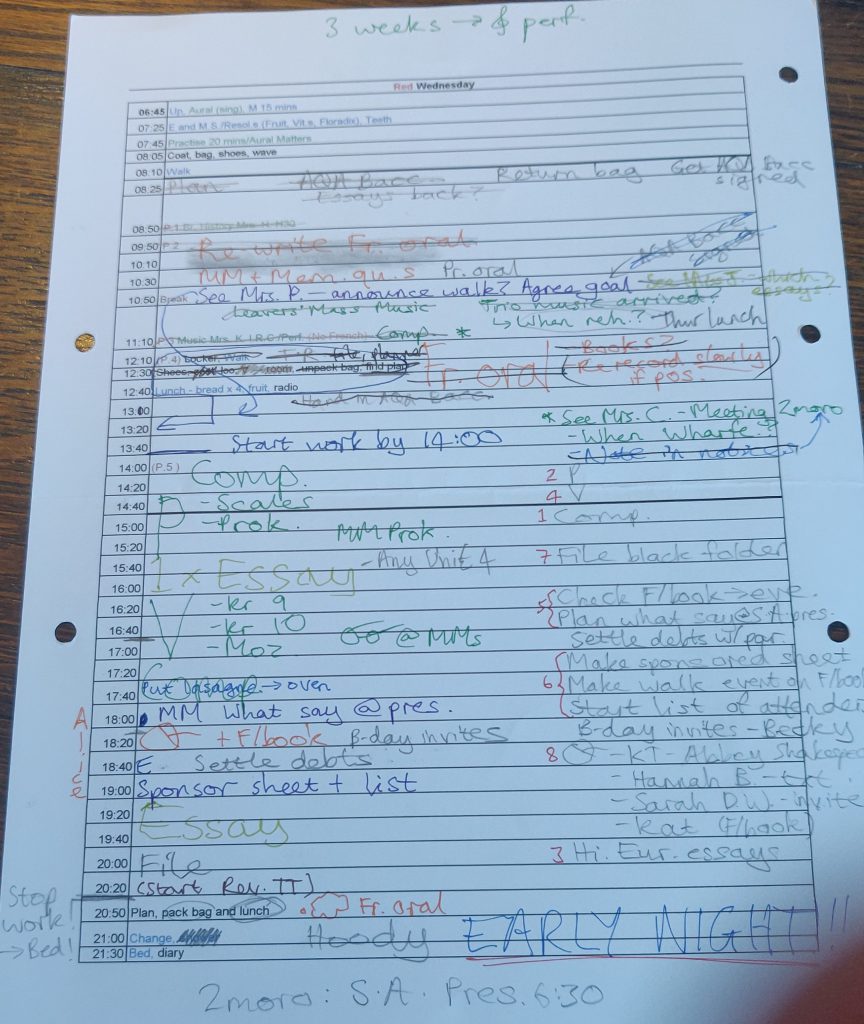

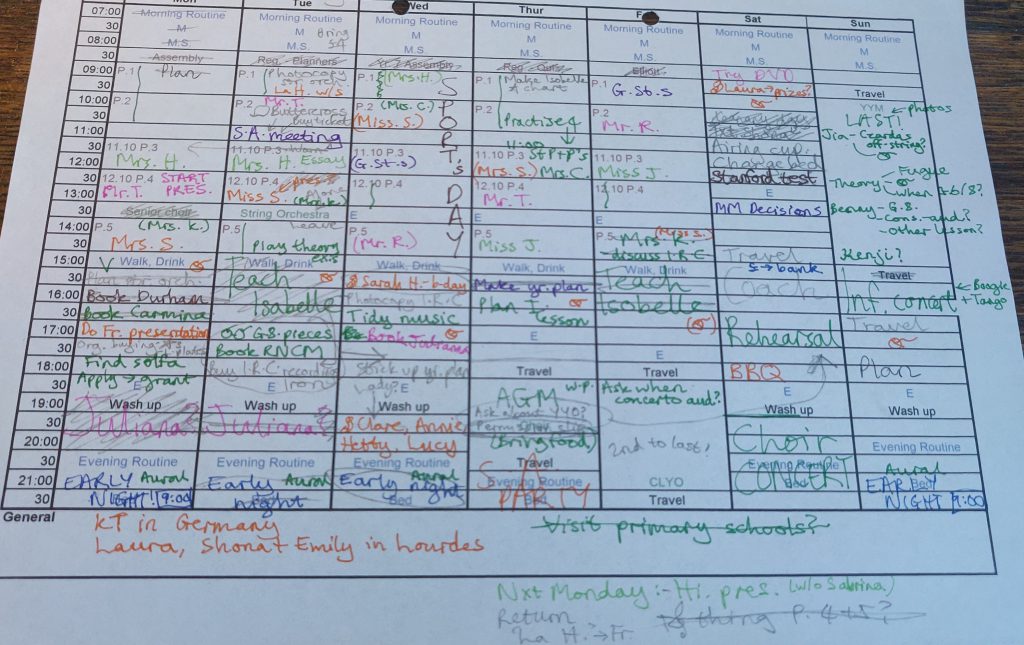

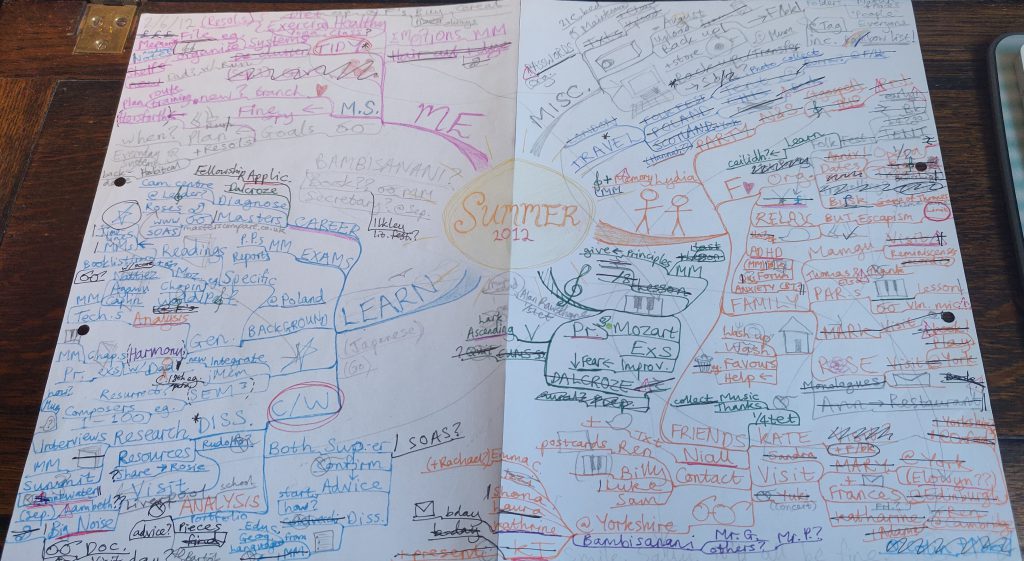

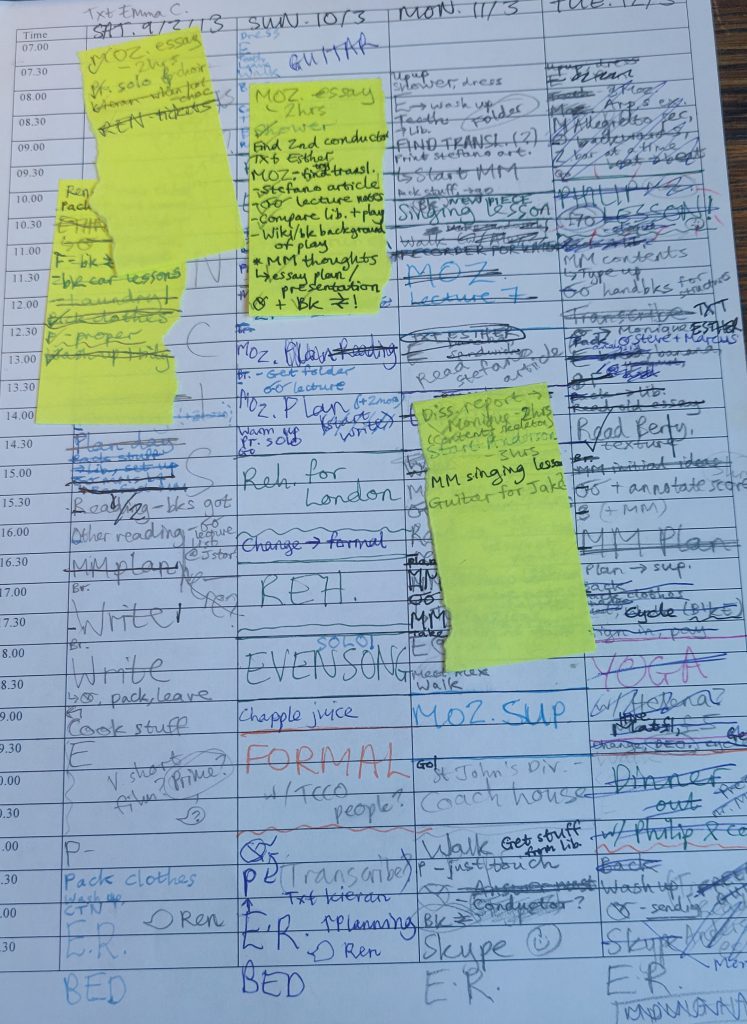

From at least my mid-teens into my early twenties, I planned my life in thirty-minute increments. It was a hellish way to live, but at the time I could only see it as optimising my life to be the best it could be. It allowed me to juggle more extra-curricular activities than should have been possible to sustain: not only violin, piano, choir and orchestra but also karate, meditation, making elaborate birthday and Christmas presents, homework and any number of school-based clubs and projects. Every moment was accounted for and there wasn’t any space for rest, relaxation, or really to think.

I honestly felt quite superior to my fellow teens. I knew I was operating on a higher plane of productivity and would out-perform them on every life metric. It was a relatively decent coping strategy for being bullied and ostracised at school—I mean, at least it wasn’t hard drugs—but it taught me all sorts of skewed lessons about how much I should expect of myself and how little my needs or emotions mattered if they didn’t fit into the preordained plan.

Of course, most of the time I wasn’t actually able to keep up with my plan. In fact often I would already be behind before I’d even finished planning. Feeling behind would always lead to despair and panic, and I would often preemptively shut down and withdraw and try to hide from all my obligations by reading or playing the Sims, all the while aware that I was just getting further behind but not having the strength to face it all.

When I was sixteen I started at a new school, and there, in my music A.S. Level class, I met Francis. I liked him, but we were very different. Basically, he was an underachiever and I was an overachiever. He never did his homework; I was a straight-A student. After that A.S. Level year, he dropped out of sixth form; I went on to Cambridge University. (We lost touch for a couple of years; I only contacted him again when I heard that he had survived a bad car crash. It’s funny how things work out.)

We started going out at the end of my first year at Cambridge. Francis was certainly very different from my Cambridge friends; visiting him during term-time was like stepping into a different world, where people actually had time to relax. I craved these tastes of a less frenetic life, but this same tendency was something I often found frustrating. When I first mentioned world travel, Francis dismissed the whole idea of ever wanting to do it, because he couldn’t see beyond how much work it would be to organise it; whereas by the time I was nineteen, I had spent my gap year organising solo trips to India, South Africa, and across Europe, and the idea of being with someone who had no interest in doing anything similar was quite worrying.

The funny thing about my feverish overachievement up to this point in my life was how, after graduation, I couldn’t seem to do it any more. I went from Cambridge straight onto job seeker’s allowance (the dole); I accepted the first admin job that would have me, even though it was three bus-rides away; my confidence was shot. Later, I tried being a counsellor and then an entrepreneur with my own coaching and tutoring business; I could only muster a lack-lustre effort for either of them. I hit my stride somewhat when I retrained as a web developer, but even now at work I am by no means a high-flyer in the team. All that drive from my student days and from when I was a teenager seem to have evaporated.

After I finally burned out around the end of university, it took me years to recalibrate my expectations and accept a slower pace of life as an adult. I am no longer looking from a place of smugness on my peers. I still struggle with ‘only’ aiming to live a ‘normal’ life without all the status-bringing achievements to which I had become accustomed. I struggle even more with realising how difficult I find it just to reach those ‘normal’ everyday standards—such as having a house that is tidy and fully painted. But I couldn’t have carried on in the way I had been even if I wanted to, and life is far happier without the constant feeling that to stop for even a minute would be disaster.

What my planning addiction was really masking was my anxiety. For a long time, I was having anxiety attacks without really realising that’s what they were. And even after letting myself learn how to do without such intensive planning practices, the anxiety hasn’t gone away.

In fact, I would say that nowadays, in a huge ironic twist, I have a worse struggle with procrastination than Francis does. I spent all my life living up to expectations, and now I can’t even handle my own expectations for myself any more. Those expectations are always too high. In order to escape my own anxiety about whether I’ll be able to do something well enough, I bury myself in reading and watching YouTube videos. I always tended towards escapism to try and deal with the pressure I was putting on myself, but if anything, without the excessive planning to try and force myself to stay disciplined I have gone even further into the spiral of avoidance and procrastination. I have spent numerous nights reading into the early hours, or until dawn; I spent years feeling stuck regarding fixing any of my problems because I could imagine every step of the long, long process of transforming our lives and our home, but without being able to imagine ever having the energy or ability to tackle them. (All of which is wasted energy, really, because as Scrum teaches us, we can’t expect the future to conform to our imagination; it’s much better to stay empirical.)

This is what perfectionism is, in my experience—no more or less than a particular form of anxiety. It’s not something good. It has eroded my ability to just do things without an enormous song and dance; I no longer trust myself to set reasonable goals or to turn my intentions into actions.

It is also a desperate illusion that one day, I can make my life perfect. Fantasies of the future are a comfort when things don’t feel like enough now. And that word, ‘enough,’ is a tricky one; I don’t like to stop looking for improvements, or accept that my own resources and reserves of energy might be limited in some way. I used to genuinely think that I should have been able to predict and prepare for every set-back—I thought that was what being proactive meant. The idea that I had done all I could, that I had done enough, was completely foreign. I could always fit more in if I just tried a bit harder.

Luckily, I have a therapist now, and I’m working on it. It has taken me a long time to come to a place where I believe in ‘enough’; that I have done enough; that I am enough even if I haven’t done enough; that I still have enough skill and confidence to change the things I want to change. Perfectionism (i.e. anxiety) is just one way that your ideas of ‘enough’ could be warped and unhelpful. It may be useful to examine whether your judgement about your achievements is truly impartial. Consider looking at your perfectionism not as some heroic strength, but perhaps as a disguised fear that has been hounding you for far too long.